Manufacturers are increasingly turning to software-defined manufacturing (SDM) – a technology model in which manufacturing software and hardware are decoupled - to substantially optimise product design and production.

BMW i Ventures’ recent investment in software-defined manufacturing specialist, Bright Machines is just one indication of the potential large manufacturers see to substantially optimise product design and production through this new technology model.

Designing production to cope with higher product variance

Manufacturing today is defined by increasing product variability and shorter product development and production cycles. For example, the number of combinations of options for the BMW 6 series was 33 times greater in 2015 than in 2008. And Volvo estimates it will have halved the time between the design and start of production of a new car model by 2020 (compared to 2012 level).

The speed with which manufacturers can reconfigure the production to a new run and thus avoid costly machine downtime – which some estimates put at $1.3 million per hour - and expensive inventory storage is critical to maintaining profit margins.

One hurdle manufacturers face is that manufacturing equipment has historically not been designed to deal with a high level of product variance. Manufacturing machines, including industrial robots, have typically required expert programmers working with code specific to individual manufacturers and machines. Once set up, machines have traditionally been expected to continue doing exactly the same task. This remains the case for some processes, but product variability has led to a much higher need to re-configure a machine within a relatively short timeframe.

In robotics, installation and integration into a production cell are estimated to account for up to two-thirds of the overall cost of an industrial robot. The software that instructs the robot’s physical movements is traditionally deeply entwined with the robot hardware that executes the movements. This means that a robot programme for drilling 3mm holes in a metal plate cannot be simply re-installed on a different manufacturer’s robot even if the new robot is supposed to carry out exactly the same task. In addition, manufacturing machines have not been integrated - so a CNC milling machine cannot ‘tell’ a grinding robot that it needs to grind an extra 1mm off a part for example.

Software-defined manufacturing provides a common language for production machines

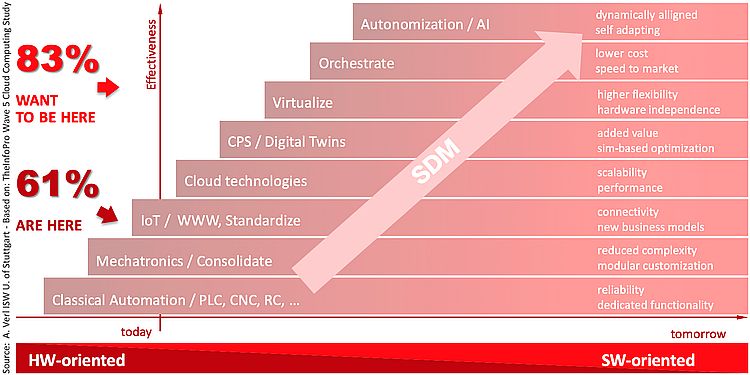

This is changing, as machines become easier to re-purpose, and as they become increasingly networked. First, robot programming has become easier, thanks to more intuitive user interfaces, and technology that enables the robot to part-programme itself by registering motion through hand-guiding by an operator. Second, a concept called software-defined manufacturing (SDM) is enabling far more flexible and faster programming not only of individual machines, but also of entire production processes.

In SDM, hardware and software are de-coupled; with the aim of ensuring that machines can be networked and configured quickly, and that code is re-usable across different machines.

SDM Benefits

SDM offers four main benefits:

- Control of multiple machines from one interface: The separation of hardware from software means that one control interface can be programmed to run multiple machines. Siemens does this with its Sinumerik controller which runs CNC machines but can be configured to also run robots. It can be programmed to run a process – such as using a CNC machine to mill a part and then using a robot to polish it – from one source, reducing coding time and increasing precision.

- Portability of robot ‘apps’: SDM works on the principle of software ‘abstraction’ which means that software is split into different layers. The aim is to make as much code as possible portable and concentrate the code that must be configured to a specific machine into one layer. This means a robot manufacturer could develop an application (for example, ‘drill a hole’) that could be downloaded by customers and quickly adapted to their specific needs (a 3mm hole) rather than having to be programmed from scratch. Ultimately, an app could be developed and deployed on robots from different manufacturers, configured through one central controller. Some robot developers are designing their robots on the principle of software abstraction, but it will be some time before robot applications are as portable as smartphone apps.

- Virtualisation: The separation of hardware from software has broader advantages. It ‘virtualises’ the physical machine, meaning that information needed to run the machine is contained within the software layer that is separate from the machine hardware. Changes can thus be made to the software representation of the machine rather than on its physical instance. This enables manufacturers to create a ‘digital twin’ of the machine on which they can try new processes and trial software updates, with no expensive downtime on the physical machine. Manufacturers can create a feedback-loop between the physical and digital versions of the machine. Physical machines generate and are subject to physical forces such vibration and the expansion of metal parts under heat that aren’t always possible to predict. Data from sensors on and around the physical machine can be analysed and fed back into the digital representation where corrections to the operating software are made, in a virtuous improvement cycle.

- Automating automation: The ultimate goal of SDM is to link all the machines in the manufacturing process not only with each other, but also with other IT systems involved in production, such as supply-chain software. The production process begins with the CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) model of the product which generates a substantial portion of the code required to produce it; triggering ERP systems to order the requisite parts, and selecting the applications required to produce it from a library – automating the process of automation.

Automotive manufacturers are probably furthest ahead in fully implementing SDM. But smaller manufacturers are also taking steps. A German timber manufacturer, for example, has integrated an industrial robot into a production process for producing wooden frames. The robot installs metal studs into the wooden frame and receives information in real time about which stud to remove from which collection station and where in the frame to place it.

Graph: © A. Verl, ISW University of Stuttgart

IFR Secretariat

The General Secretariat is responsible for the daily management of IFR and the coordination of all major activities, events and collaboration. The General Secretariat handles all questions regarding IFR membership.

Dr. Susanne Bieller

IFR General Secretary

Phone: +49 69-6603-1502

E-Mail: secretariat(at)ifr.org

Silke Lampe

Communication Manager

Phone: +49 69-6603-1697

E-Mail: secretariat(at)ifr.org

Credits · Legal Disclaimer · Privacy Policy ·World Robotics Terms of Usage · © IFR 2026